No Longer Human Worldwide: How Osamu Dazai’s Classic Is Read, Translated, and Reimagined (2026 Guide)

TrendWordAI Editorial Note (neutrality-first): This guide prioritizes accuracy and source transparency. It separates verifiable facts (publication/edition data) from interpretation, and it avoids promotional or financial recommendations.

Published: January 12, 2026 (JST)

Last updated: January 12, 2026 (JST)

Ad disclosure: This article contains advertisements. TrendWordAI may receive compensation from ads shown on the site. This does not change our editorial approach.

Content note: No Longer Human depicts self-harm, addiction, sexual exploitation/sexual violence, and suicidal ideation. This guide discusses themes and reception without graphic detail.

- Overview (5W1H)

- Timeline: Key milestones in global reception (selected)

- The structure: why the “frame” matters more overseas than you might expect

- Three recurring overseas interpretive lenses (and what each lens misses)

- Translation is interpretation: why the English title debate matters

- Pop-culture gateways: how anime, manga, and graphic adaptations reshape global Dazai

- Common misconceptions in overseas discussions (and how to correct them without gatekeeping)

- How to read No Longer Human in 2026: a practical cross-cultural toolkit

- Choosing an English edition: what to look for (without telling you what to buy)

- Discussion toolkit (book clubs, classrooms, online communities)

- FAQ

- Q1. Is No Longer Human autobiographical?

- Q2. Why are there multiple English titles?

- Q3. Which translation is “best”?

- Q4. Why is Dazai so visible in anime/manga spaces?

- Q5. Does the novel endorse self-destruction?

- Q6. Is “shame culture” the main explanation?

- Q7. What is the most important thing not to miss?

- Q8. What should I read next for context (not just the same mood)?

- Summary (key takeaways)

- References (Official / Academic / Major Media)

Osamu Dazai’s No Longer Human (人間失格, Ningen Shikkaku) is widely introduced outside Japan as an “alienation classic”—a confessional story about a man who feels incapable of belonging to the human world. That framing explains the book’s immediate emotional impact, but it’s only part of why the novel travels. International readers don’t just read Dazai through a different language; they read through different cultural assumptions about confession, shame, mental health, family obligation, and what a “classic” is supposed to do.

As a result, No Longer Human becomes a slightly different book depending on where—and how—you encounter it: through a 1950s English translation that shaped decades of reception, through newer retranslations that update voice and framing, or through pop-culture gateways (anime, manga, graphic adaptations) that prime readers for a particular “dark classic” mood.

This guide maps the international reception of No Longer Human in a practical way. It offers:

-

a structure refresher (why the frame matters),

-

three recurring interpretive lenses used in English-language discussion,

-

how translations and titles steer meaning,

-

how pop culture and online communities reshape expectations, and

-

a reading + discussion toolkit you can use across cultures.

Overview (5W1H)

-

What: A global reader’s guide to how No Longer Human is read, marketed, and debated in translation—especially in English.

-

Who: Osamu Dazai (1909–1948), plus the publishers, translators, critics, educators, and online communities that keep reframing the work.

-

When: Originally published in Japan in 1948. English reception formed around a major translation first published in 1958, later consolidated through widely circulated editions, and renewed through new translations and editions in 2018 and 2024.

-

Where: Global, with strong visibility in North America and the UK through English-language publishing, universities, bookstores, and fandom ecosystems.

-

Why it persists: The novel’s themes of masking and social fear translate well across cultures, while its framed-document structure invites lasting debates about autobiography versus crafted narrative.

-

How overseas meaning is shaped: Through translation choices, paratext (titles, covers, blurbs, introductions/afterwords), and gateway media (anime/manga/graphic adaptations) that pre-shape “what kind of book” readers think they’re getting.

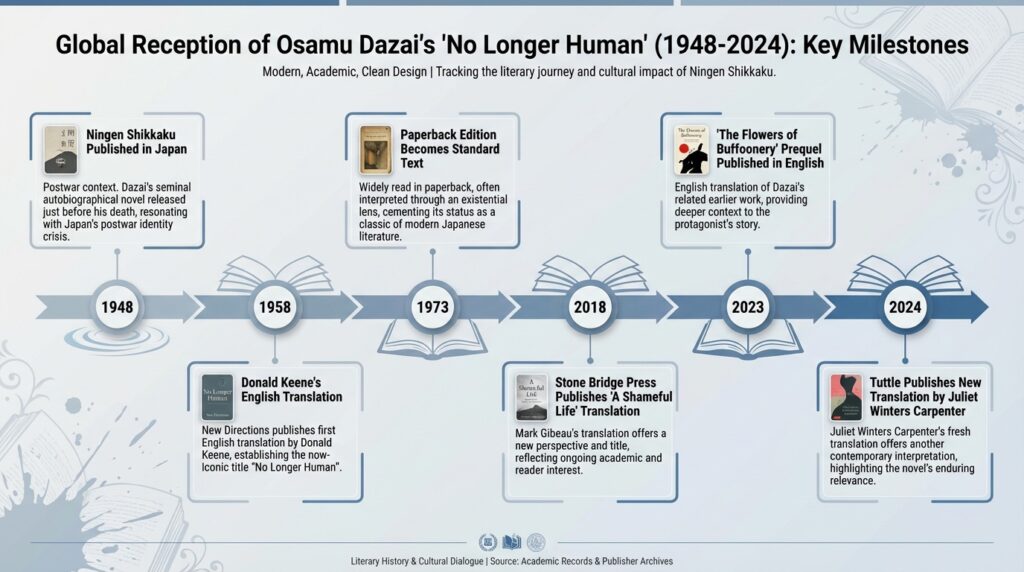

Timeline: Key milestones in global reception (selected)

【タイムライン】1948年から2024年までの海外受容の主要マイルストーン(横軸年表形式、各年代に翻訳版・適応作品・文化的影響を配置)

| Year | Milestone | Impact on overseas reception |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | Ningen Shikkaku published in Japan | Postwar context becomes a debate point in translation: historical reading vs. “universal alienation.” |

| 1958 | Donald Keene’s English translation first published by New Directions | Established the widely recognized English title No Longer Human and a durable “alienation classic” framing for decades. |

| 1973 | Paperback circulation of the Keene translation | Helped normalize the book as a readily available “classic” for general readers and classrooms. |

| 2018 | Mark Gibeau translation published by Stone Bridge as A Shameful Life | Title shift foregrounds “shame/confession” over “status/condition,” changing how readers approach the same events. |

| 2023 | The Flowers of Buffoonery (related Dazai work) published in English | Renewed interest in Dazai’s “buffoon/clown” motif, expanding global reading beyond a single title. |

| 2024 | Juliet Winters Carpenter publishes a new translation titled No Longer Human (Tuttle) | Coexisting translations encourage comparison: readers begin asking which “Yozo voice” they are reading. |

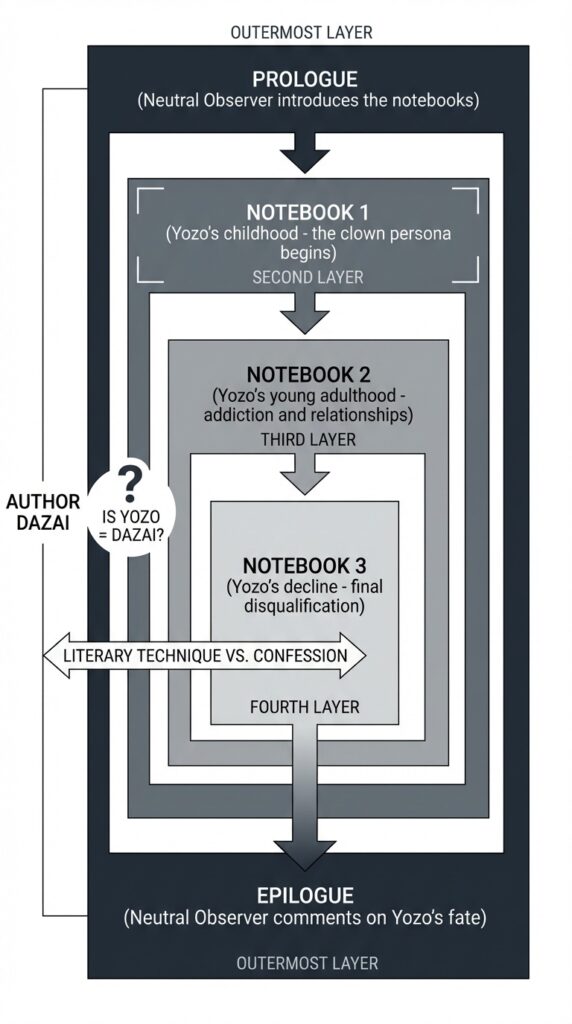

The structure: why the “frame” matters more overseas than you might expect

Many overseas discussions start from the book’s “confessional feel.” That’s understandable—but the structure complicates confession on purpose.

The nested-document design (frame → notebooks → frame)

No Longer Human presents itself as a set of notebooks written by Yozo Oba, introduced and concluded by an observer-like frame voice. That design creates two reading habits common in international reception:

-

Confession-first reading: “This must be the author speaking directly.” Readers collapse Yozo and Dazai into one identity.

-

Frame-first reading: “Someone is presenting and shaping this voice for us.” Readers treat the work as staged narration, not raw diary.

The second habit matters because it explains why No Longer Human can feel both intimate and constructed at the same time. Even if you take biography as context, the text still asks: Who is speaking? Who is framing? Who is being made to look at whom?

【図解】小説の入れ子構造(プロローグ→ノート1・2・3→エピローグ)を視覚化し、「額縁技法」がどう読者の解釈を複雑にするかを示す図

The “clown/buffoon” as exportable social technology

A recurring theme in English descriptions is Yozo’s “clownery”—performing normality to avoid being exposed. Publisher blurbs highlight it because it’s instantly legible to non-Japanese audiences. In contemporary overseas reading, the same behavior is often mapped onto modern vocabulary (masking, people-pleasing, performative sociability).

A useful way to keep this grounded is to treat “clowning” not as a single personality trait but as a social technology:

-

it gains safety and approval,

-

it blocks intimacy,

-

it delays help, and

-

it can fail violently when the social environment changes or when the performance collapses.

This is one reason the novel keeps feeling “current” to new generations of international readers: the fear of other people, expressed as daily acting, travels.

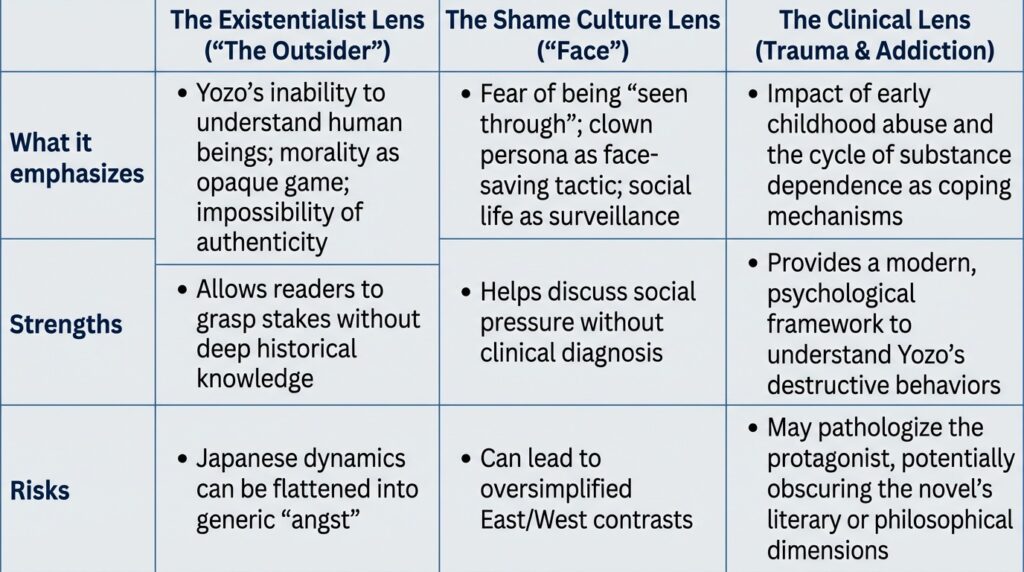

Three recurring overseas interpretive lenses (and what each lens misses)

International reception is not one conversation. It is a set of reading communities—publishers, reviewers, classrooms, and online fandoms—each with default assumptions. The three lenses below recur widely in English-language talk.

【表】三大解釈レンズの比較表(実存主義レンズ / 恥・フェイスのレンズ / 臨床レンズ:各レンズの強調点・強み・リスクを3列で整理)

1) The existentialist lens (“the outsider canon”)

Many English readers enter No Longer Human through a familiar shelf: existentialism, confessional modern classics, and “outsider narrator” literature. Publisher positioning has reinforced this pathway.

What it emphasizes

-

Yozo’s repeated claim that he cannot understand “human beings.”

-

Ordinary morality as an opaque social game.

-

Authenticity as difficult because social life requires a mask.

Strengths

-

Gives non-specialist readers immediate orientation.

-

Fits comparative literature conversations.

What it can miss

-

Japan-specific social pressures and historical context can become a vague “modern angst” background.

-

The frame can get reduced to “real confession,” when the book is doing more than confession.

2) The shame / face / performance lens

Another major pathway centers shame as a relational mechanism: fear of exposure, dependency on approval, and the exhausting labor of performing acceptability. Overseas readers sometimes reach for simplified “shame culture” explanations; academic discussion tends to treat those explanations as debated rather than definitive.

What it emphasizes

-

Fear of being “seen through.”

-

The clown persona as face-saving and intimacy-blocking.

-

Belonging as surveillance rather than community.

Strengths

-

Helps readers discuss social pressure without turning everything into a medical diagnosis.

-

Highlights why the novel is not only “internal suffering” but also social fear.

What it can miss

-

Oversimplified East/West contrasts (“Japan = shame, West = guilt”) can distort the novel’s complexity.

-

Shame can be treated as a cultural label rather than something produced by specific relationships and institutions.

3) The psychological / clinical lens (trauma, addiction, narration)

A third pathway reads the notebooks as a psychological document: dissociation, addiction, self-sabotage, unstable narration, and spiraling behavior. This lens often intersects with Dazai’s widely mythologized biography.

What it emphasizes

-

Unreliable narration and escalation.

-

Stigma, coping, and self-destructive cycles.

-

The cost of “masking” when it becomes a trap.

Strengths

-

Encourages attention to how the spiral is built as narrative structure.

-

Supports careful discussions of harm without glamorization.

What it can miss

-

Turning the work into a case file (“Yozo has X”) can flatten irony, framing, and social critique.

-

Biography can become a substitute for reading technique.

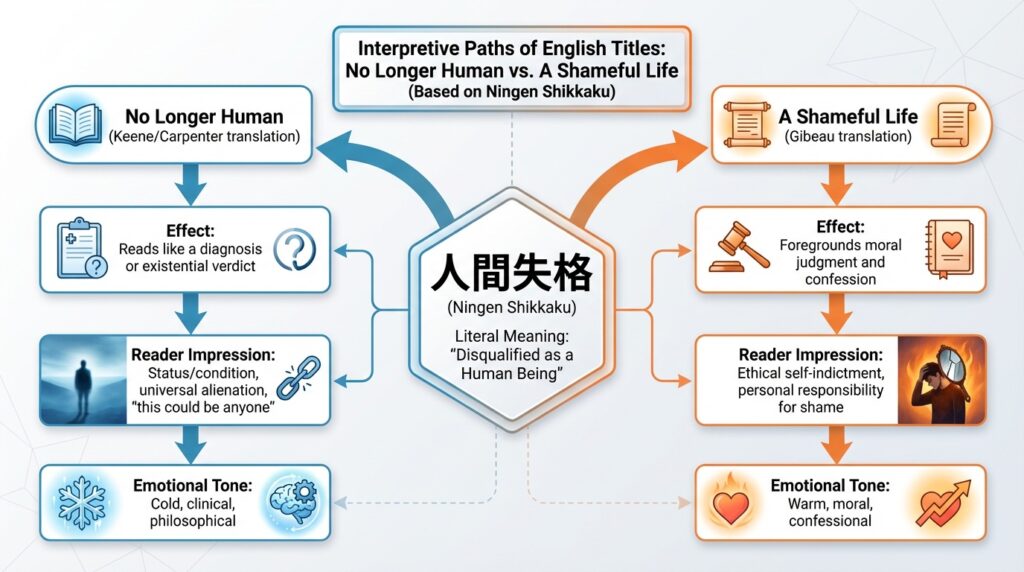

Translation is interpretation: why the English title debate matters

The title is not a neutral label. It is the first argument the book makes to a reader.

【図解】タイトル比較図(”No Longer Human” vs “A Shameful Life”:各タイトルが読者にどう印象を与えるか、矢印で流れを示す)

“No Longer Human”: condition, status, or verdict

The longstanding English title No Longer Human reads like a condition or existential verdict. Keene’s translator note (in the front matter of widely circulated editions) points out that a more literal rendering is closer to “Disqualified as a Human Being,” which can shift the feel from mood to social judgment.

How it primes readers

-

“This is an existential condition.”

-

“This could be universal, cross-cultural.”

“A Shameful Life”: moral confession and social judgment

The title A Shameful Life foregrounds shame and confession. Even without changing the plot, the framing changes the reader’s posture:

-

it can feel more like ethical self-indictment,

-

less like an existential status,

-

and more like a moral narrative the reader is asked to evaluate.

Why retranslations keep happening (without over-mystifying it)

Retranslations are common for classics, and they don’t always signal “the old one was wrong.” Practical reasons include:

-

Language aging: a 1950s voice can feel distant in 2026.

-

Editorial framing shifts: introductions/afterwords and cover copy change how first-time readers interpret tone.

-

Market segmentation: one edition aims for classrooms; another aims for general readers; another aims for pop-culture gateway audiences.

-

Cultural vocabulary changes: mental-health language and identity discourse change what readers notice first.

A simple rule: overseas interpretation often begins before page one—with title, cover, and marketing copy.

Pop-culture gateways: how anime, manga, and graphic adaptations reshape global Dazai

A growing share of overseas readers do not meet Dazai through school first. They meet him through adjacent media—and then backtrack to the novel.

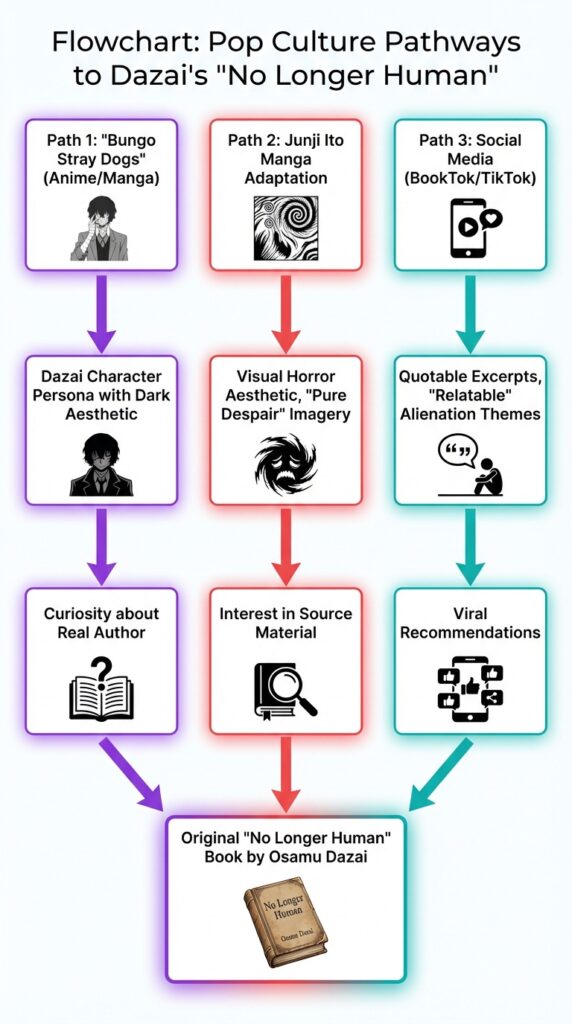

【フローチャート】ポップカルチャー経路図(読者の入口→アニメ/マンガ/グラフィック→原作小説への到達パスを複数矢印で図示)

Bungo Stray Dogs and “Dazai as character”

English-language publishers increasingly acknowledge Bungo Stray Dogs as a gateway: readers recognize the name “Dazai” via a fictional character and then seek the original author.

What this changes

-

The author becomes a persona: “Dazai” is consumed as mood and character first, then mapped back onto the novel.

-

Readers may arrive expecting stylized darkness rather than a framed document narrative that carefully manages distance and observation.

Junji Ito and the “classic reimagined” route

Graphic adaptations—especially Junji Ito’s No Longer Human—have circulated strongly in English-language manga markets. This route can attract readers who might not otherwise pick up a postwar Japanese novel.

What this changes

-

Readers may treat the story as an aesthetic object (“beautiful despair,” horror mood) rather than a structured argument about performance, social fear, and narrative framing.

-

Visual interpretation can harden one reading (“pure despair”) even when the prose includes shifts in tone, irony, or social observation.

Social media discovery: one factor among several

It is common to credit TikTok/BookTok or short-form platforms for renewed attention. In practice, it is safer—and more accurate—to treat social media as one amplifier among several:

-

retranslations and new editions,

-

adaptation ecosystems,

-

recommendation loops across communities,

-

and the book’s easily excerpted confessional style.

The key point is not “a platform revived Dazai,” but that global visibility now operates through mixed channels—and pop-culture entry points shape what readers expect the novel to deliver.

Common misconceptions in overseas discussions (and how to correct them without gatekeeping)

Misconception 1: “It’s just Dazai’s diary.”

The confessional tone encourages autobiography-first reading. But conflating author and narrator can erase the frame and reduce technique to “life story.”

Correction strategy

-

Say: “Biography may be context; narration is technique.”

-

Use the frame as evidence: someone is presenting these notebooks, and that presentation is part of the meaning.

Misconception 2: “The novel romanticizes self-destruction.”

Overseas reception can swing between glamorization and moral condemnation. A grounded approach recognizes that the narrative shows cost—often without catharsis.

Correction strategy

-

Separate depiction from endorsement.

-

Discuss how the book positions the reader (pity, judgment, voyeurism) rather than turning the conversation into moral scoring.

Misconception 3: “Japan is a ‘shame culture,’ so the book is about that.”

This collapses complex debates into a slogan and risks cultural stereotyping.

Correction strategy

-

Use “shame/face” as one lens, not a national diagnosis.

-

Emphasize relational detail: shame in the novel is produced by specific relationships, institutions, and social expectations.

How to read No Longer Human in 2026: a practical cross-cultural toolkit

This section is designed to be used while you read—especially if you’re reading in translation.

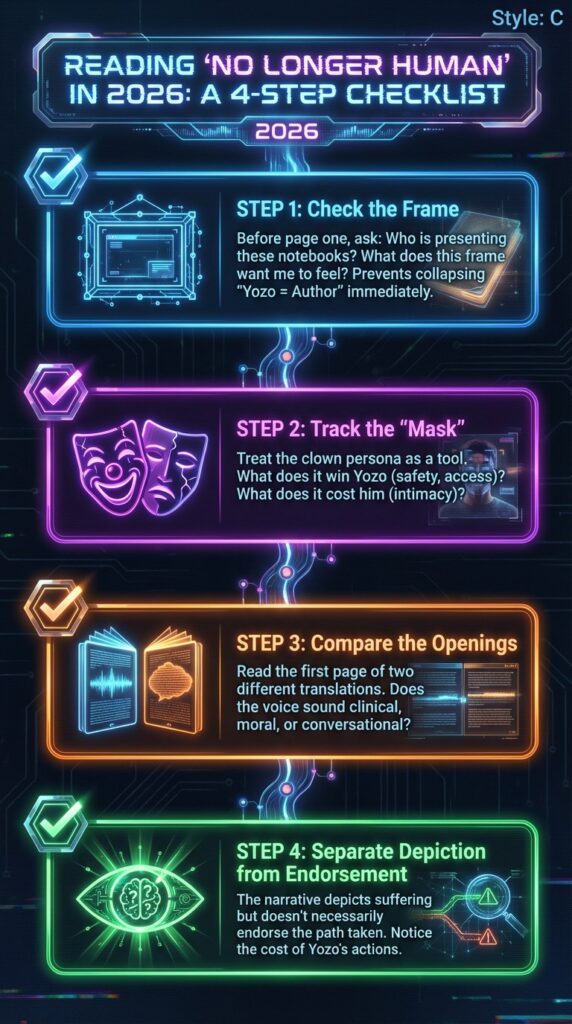

【チェックリスト】2026年版読解ガイド(Frame確認→Mask追跡→翻訳比較→描写と推奨の分離)

Step 1: Identify the frame before the confession

Before you interpret “what Yozo means,” ask:

-

Who is presenting these notebooks?

-

What is the frame encouraging me to feel (sympathy, disgust, curiosity, moral evaluation)?

-

What does the frame withhold?

A surprising amount of overseas misreading comes from skipping this step.

Step 2: Track the mask as a tool with a cost

Instead of reading clowning as a personality quirk, treat it as a strategy:

-

What does it achieve socially (approval, safety, access)?

-

What does it block (honesty, intimacy, rescue)?

-

When does it fail, and what changes at that moment?

This makes the novel legible across cultures without forcing it into a single psychological label.

Step 3: Do a short translation comparison (even if you only have one copy)

If you can access multiple editions (library, bookstore browsing, previews), compare the opening pages:

-

Does the English voice feel clinical, moral, or conversational?

-

Does it feel like testimony, irony, or both?

-

Does the title prime “condition” (No Longer Human) or “confession” (A Shameful Life)?

Even a few paragraphs can reveal how translation shapes “who Yozo is” on the page.

Step 4: Separate depiction from endorsement

This is especially important for a novel with heavy themes.

-

The book can be meaningful without being a lifestyle or aesthetic.

-

If a conversation begins to glamorize harm, redirect to technique and consequences.

Step 5: Keep one context anchor (avoid overload)

Choose one anchor and stick to it:

-

Historical anchor: postwar Japan as a background of discredited certainties and social redefinition.

-

Literary anchor: framed confession as craft, not pure diary.

-

Publishing anchor: paratext and packaging as interpretive forces.

You do not need all three to read well; one is enough to prevent “vibes-only” reception.

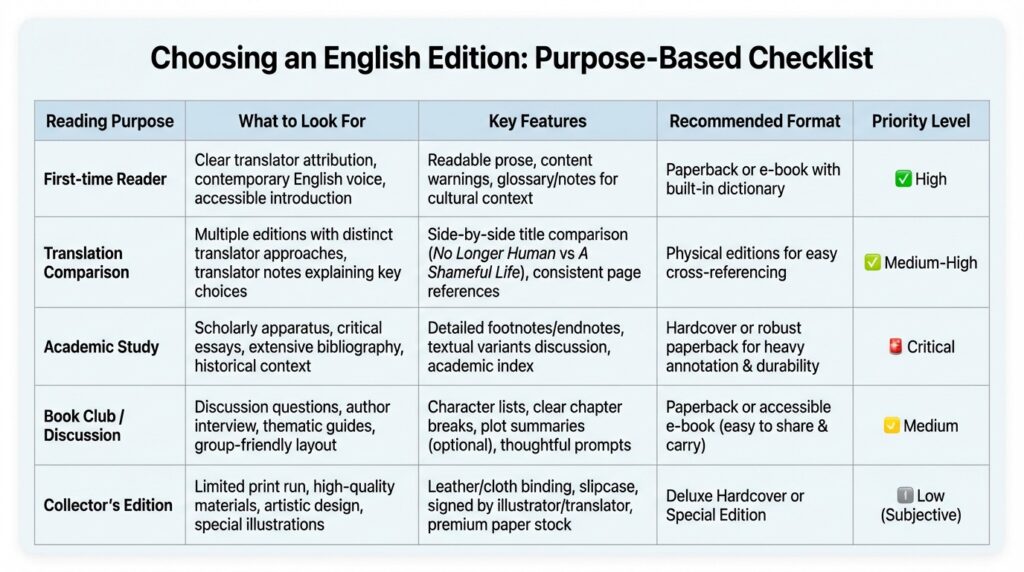

Choosing an English edition: what to look for (without telling you what to buy)

This guide avoids product recommendations. Instead, it offers a neutral checklist for selecting an edition that fits your reading purpose.

【表】英語版の選び方(目的別チェック表:授業用 / 初読者 / 翻訳比較 / 研究・引用)

If you’re reading for the first time

Look for:

-

clear translator attribution and edition information,

-

an introduction/afterword that explains the frame without over-biographizing,

-

readable contemporary English if older prose feels distant to you.

If you want to compare interpretations through translation

Look for:

-

editions with distinct titles and translator approaches,

-

translator notes (even short ones) explaining key choices,

-

consistent page references if you plan to discuss in a group.

If you’re reading in a classroom or book club

Look for:

-

accessible discussion prompts or contextual notes,

-

content note clarity (so participants are not surprised),

-

stable availability so everyone can use the same edition.

If you’re citing academically

Look for:

-

a stable publisher edition with clear bibliographic metadata,

-

translator name, publication year, and edition details,

-

consistent pagination and a clear distinction between novel text and commentary.

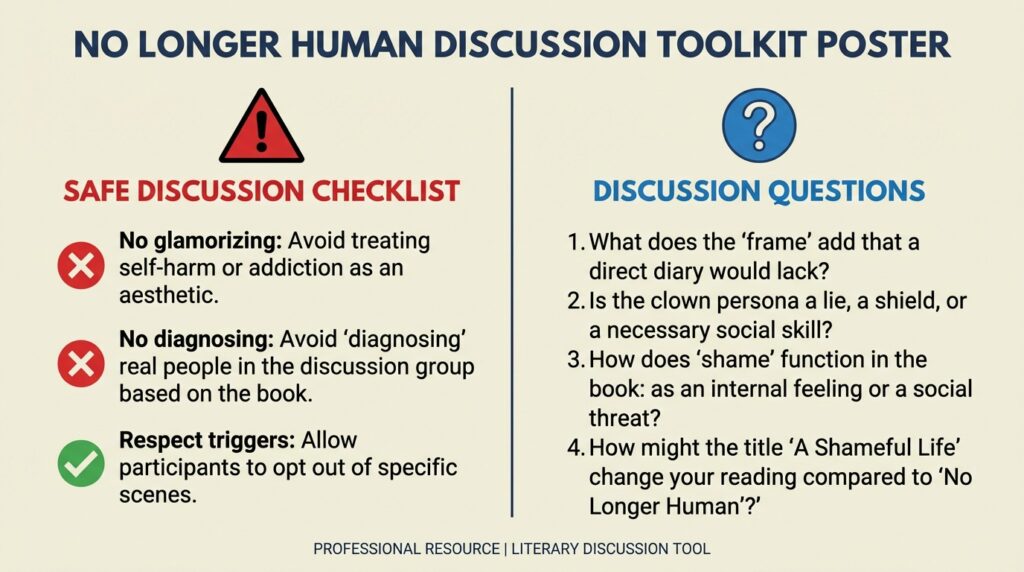

Discussion toolkit (book clubs, classrooms, online communities)

Some global reading communities approach No Longer Human as identity mirror, mood text, or “dark classic.” That can produce powerful identification—but also risks glamorization or simplistic cultural stereotyping. The toolkit below is designed to keep discussion grounded.

【表】ディスカッションツールキット(Safe Discussion Checklist + Questions)

Safe discussion checklist (recommended)

-

No glamorizing: Avoid treating self-harm/addiction as aesthetic proof of depth.

-

No diagnosing people: Do not “diagnose” group members or public figures via the book.

-

Respect triggers: Allow participants to skip questions or scenes without explanation.

-

Focus on technique: When discussion becomes moral scoring, return to frame, voice, and consequence.

If the subject matter feels personally activating, consider reading with support and taking breaks. If you feel in immediate danger, contact local emergency services or crisis support in your country.

Discussion questions that travel across cultures

-

What does the frame add that a direct diary would lack?

-

When does Yozo appear most aware of manipulating the reader?

-

Is the clown persona a lie, a shield, a social skill, or a trap?

-

Where do you see tenderness, and why doesn’t it stabilize the story?

-

How does shame function: inner feeling, social threat, or moral judgment?

-

How does translation voice change your sense of Yozo’s agency?

-

What does the novel imply about “normal life” as a demand rather than a fact?

-

What does the ending ask the reader to do—judge, mourn, detach, forgive?

-

What parts feel universal, and what parts feel historically specific?

-

If you arrived via pop culture, what expectations did you bring—and did the novel confirm or resist them?

FAQ

Q1. Is No Longer Human autobiographical?

Many readers describe it as semi-autobiographical, and Dazai’s biography is widely discussed. However, autobiography is not a substitute for reading the frame and the constructed voice. A useful approach is: biography may be context; narration is technique.

Q2. Why are there multiple English titles?

Different translators and publishers choose different framing. “No Longer Human” primes a condition/status reading; “A Shameful Life” primes a confession/shame reading. Titles are interpretive decisions.

Q3. Which translation is “best”?

There is no single best translation for every reader or purpose. Retranslations exist because language ages, contexts change, and publishers frame classics differently. Comparing openings is often more informative than debating “best.”

Q4. Why is Dazai so visible in anime/manga spaces?

Gateway media makes literary classics discoverable to broader audiences. This can expand readership while also shaping expectations (for mood, character persona, and “dark classic” framing).

Q5. Does the novel endorse self-destruction?

Depiction is not endorsement. The narrative can be read as exposing the costs and consequences of a spiral rather than romanticizing it. Discussions benefit from focusing on technique and consequence.

Q6. Is “shame culture” the main explanation?

It can be one lens, but treating it as a single national explanation risks stereotyping and oversimplification. The novel’s shame dynamics are relational and situational, not a cultural slogan.

Q7. What is the most important thing not to miss?

The frame. It changes how confession is read, how sympathy/judgment is produced, and how the reader is positioned.

Q8. What should I read next for context (not just the same mood)?

If you want broader Dazai context, consider reading other major works available in translation, or scholarly context on narration and modern Japanese literature. Choosing “context” rather than “more darkness” often leads to better understanding.

Summary (key takeaways)

-

International reception is plural: existential, shame/face, and clinical lenses recur, and each highlights different parts of the same text.

-

Translation is interpretation: titles and paratext prime meaning before page one.

-

Pop-culture gateways are now part of the novel’s global life: they expand readership and reshape expectations.

-

The frame is the strongest reading tool: it prevents autobiography-only reduction and clarifies how the novel constructs reader response.

-

As of January 2026, multiple major English editions coexist: comparison culture is now a core part of overseas reception.

References (Official / Academic / Major Media)

(Accessed January 12, 2026. URLs are listed only here.)

-

Encyclopedia Britannica — “Dazai Osamu.” Updated/revised date shown on page. Accessed Jan 12, 2026.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Dazai-Osamu -

New Directions Publishing (official) — “No Longer Human” (Osamu Dazai; Donald Keene translation). Accessed Jan 12, 2026.

https://www.ndbooks.com/book/no-longer-human/ -

Internet Archive (edition scan) — No Longer Human (Osamu Dazai; Donald Keene translation). Front matter includes publication/rights notes. Accessed Jan 12, 2026.

https://archive.org/download/november2020booksalex/Books%20November%202020/Osamu%20Dazai%20-%20No%20Longer%20Human-New%20Directions%20%281973%29.pdf -

Stone Bridge Press (official) — “A Shameful Life (Ningen Shikkaku)” (Osamu Dazai; Mark Gibeau translation). Publish date shown on page. Accessed Jan 12, 2026.

https://www.stonebridge.com/catalog/a-shameful-life -

Tuttle Publishing (official) — “No Longer Human (9784805317426)” (Osamu Dazai; new translation by Juliet Winters Carpenter). Publish date shown on page. Accessed Jan 12, 2026.

https://tuttlepublishing.com/japan/no-longer-human-9784805317426 -

The Atlantic — Jane Yong Kim, “‘No Longer Human’ Captures the Paradox of the Social Loner.” Published date shown on page. Accessed Jan 12, 2026.

https://www.theatlantic.com/books/archive/2023/07/osamu-dazai-no-longer-human-flowers-of-buffoonery-book-review/674572/ -

JSTOR — “A Reconsideration of the Culture of Shame.” Bibliographic record on JSTOR. Accessed Jan 12, 2026.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/42800062 -

Princeton University Press (preview / catalog) — Alan Stephen Wolfe, Suicidal Narrative in Modern Japan: The Case of Dazai Osamu. Publication details in publisher materials. Accessed Jan 12, 2026.

https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9781400861002_A23705048/preview-9781400861002_A23705048.pdf -

VIZ Media (official blog) — “No Longer Human Manga by Junji Ito Review.” Published date shown on page. Accessed Jan 12, 2026.

https://www.viz.com/blog/posts/no-longer-human-manga-by-junji-ito-review -

VIZ Media (official blog) — “Creator Profile: Junji Ito.” Published date shown on page. Accessed Jan 12, 2026.

https://www.viz.com/blog/posts/creator-profile-junji-ito

この記事はきりんツールのAIによる自動生成機能で作成されました

【PR】

コメント